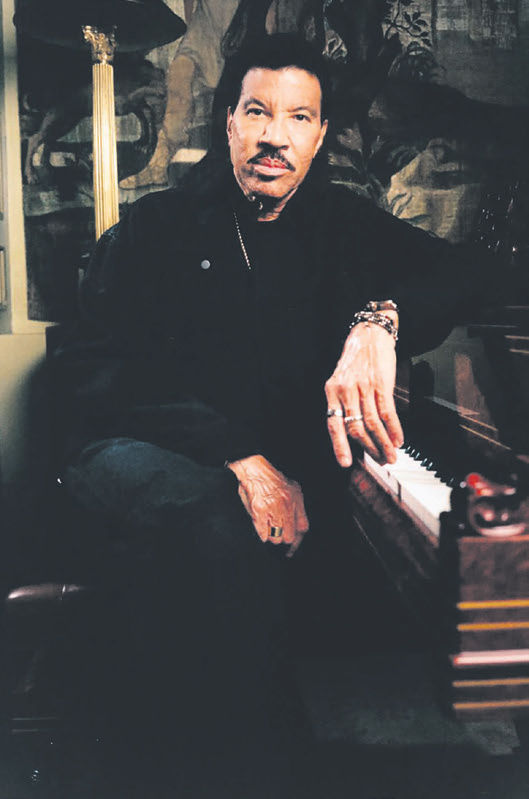

How a sentimentalist like Lionel Richie learned to ‘attack the lion’

- The San Juan Daily Star

- Oct 6, 2025

- 5 min read

By ELISABETH EGANS

Lionel Richie paced a hallway in his gargantuan house in Beverly Hills, staring at a video on his manager’s phone. It showed copies of his memoir, “Truly,” zipping down a conveyor belt at a printing plant in Virginia.

Richie shook his head slowly, hand over mouth, as if beholding a newborn.

Behind him were two sitting rooms, each outfitted with a grand piano. One had shelves lined with awards climbing all the way to the ceiling. The other had a pedestal bearing a tooled leather guest book signed by Richie’s famous friends, including Pharrell Williams, Sidney Poitier, Jackie Chan and Gregory Peck.

Richie, 76, had just returned from a European tour and was about to embark on another in South America. Over the past 50 years, he has sold more than 100 million albums, been a voice of reason on “American Idol” and performed in sold-out stadiums before audiences so big they appear oceanic from the stage.

And yet, face to face with his own life story, Richie was speechless.

“This is not a book about who I met and who I knew,” he said, striding in jaunty orange sneakers into yet another room. “It was about fear. Can you overcome your worst fears and move forward?”

‘Twice as Tough’

“Truly” is a satisfying 463-page brick crammed with childhood memories, music industry anecdotes and 25 pages of photos.

It follows Richie from his boyhood in Tuskegee, Alabama (he dreamed of becoming an Episcopal priest); to his years playing saxophone and singing for The Commodores (he slept under a table during the band’s first summer in New York City’s Harlem section); his breakout as a solo artist (with “Hello,” “Stuck On You” and the song that gives the book its title); and his current incarnation as a troubadour philosopher, renowned for his staying power.

Richie’s disappearance from the public eye for nearly a decade only gets two chapters in the book, but they’re its most vulnerable and powerful. This was the period when he started to stare down insecurities he’d carried from Tuskegee to Los Angeles.

He writes about his fear that, after The Commodores, he’d never have another hit. His fear of missing out; of letting his family down; of not having a backup plan. And his struggles with stage fright, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and depression.

“Truly” isn’t a sad book, but it is a candid one. And Richie is refreshingly frank on the subject of race.

Back in the day, Tuskegee was, as Richie describes it, a haven for “the best doctors, the best lawyers, the best surgeons, who just happened to be Black.”

In the book, he recalls a 1986 interview with Barbara Walters, tentatively titled “Lionel Richie, Rags to Richie” until she visited the gracious college-adjacent home that was deeded to the Richie family by heirs of Booker T. Washington. (Richie’s grandparents were also friends with George Washington Carver.)

He writes, “We all understood that if you were Black, you had to be twice as good as the standard. You had to withstand doubt and overcome obstacles that were twice as tough.”

In our conversation, Richie kept coming back to the idea of fortitude: “My dad used to say, ‘Are you standing up? Or are you hiding behind the couch? What’s the similarity between a hero and a coward? They were both scared to death. One stepped forward, and one stepped back.’”

‘The Little Boy with Glasses’

Richie’s mother was an English teacher. His grandmother was a classical pianist. “He grew up in a community that was oriented toward books and intellectual life and people who put words on the page,” said Elizabeth Mitchell, Richie’s editor at HarperOne.

Still, he had some trepidation about writing a memoir. When he committed to it, he considered taking a page from Cher — going with a two volumes — but his publisher and his collaborator, Mim Eichler Rivas, gently nixed the notion.

(“My publishers didn’t like the idea either,” Cher said in an interview, “but then they realized it couldn’t be one book. You wouldn’t be able to lift it.”)

At first Richie and Rivas worked together for a few hours each afternoon. Then their sessions migrated to Richie’s preferred time slot, beginning around one o’clock in the morning and ending near dawn.

“I have to be there when God is available,” Richie said. “No lawyers. No managers. No agents. No press. No nothing.”

Richie told stories, and Rivas asked questions and recorded.

There were minor disagreements, as when Rivas inserted a word like “flabbergasted,” Richie said. “I’d go, ‘Mim. I’m Black.’” This was not a word he’d use.

The hardest part, Richie joked, was “admitting to myself and to the rest of the world” that he was not a jock, a standout student or even especially popular during his school days.

“He was the little boy with glasses,” said Ronald LaPread, who grew up with Richie and played bass for The Commodores. “He was kind of skinny. Very insignificant.”

Richie recalled the moment when the tide started to turn, at a talent show at Tuskegee College (now a university).

“The greatest line I ever heard, coming out of a girl’s mouth: ‘Sing it, baby!’” Richie said. “It was one of those things where, OK, I think I’m getting kind of cool. I had never been cool in my life.”

LaPread said, “Not only did we have a decent frontman, he was a hell of a songwriter. It all turned into sweet sugar.”

Tempted as Richie was to tread lightly on painful subjects, he knew he’d be wasting time if he didn’t dig into the hard stuff in his book.

He has an axiom for this too: “If you run from the lion, the lion will chase you. If you attack the lion, the lion will run away.”

‘God Has Your Next Move’

Reading “Truly,” one can sense Richie’s discomfort — and his determination to be fair — as he delves into the dissolution of two marriages and The Commodores. (“I’m sure it wasn’t easy for him and it wasn’t easy for us either,” LaPread said. “All we knew was each other.”)

Richie gets his lightness back when he describes “We Are the World,” which he wrote with Michael Jackson and recorded during an all-night marathon session with a bevy of luminaries in 1985.

“‘We Are the World’ changed my life,” Richie writes. “It made me ask, Well, if I’m in my championship season, what good can I do with it?”

The record sold 800,000 copies in three days, according to the book, and raised $80 million for famine relief in Africa.

In the aftermath, Richie felt like he was on the nose of a rocket. Everyone else in his orbit was safe inside — agents, manager, family, friends.

Then Richie’s father died. His first marriage ended, publicly and painfully. His voice gave out.

“I didn’t know you can disintegrate with the rocket,” he said.

Richie had what he described as a “nervous breakdown.” In 1991, he spent five days alone in Jamaica, sitting in a beach chair and drinking Cristal as the tide crept up around him. Each night, he writes, “the hotel staff would come out, pick me up in the chair, and retrieve my empty champagne bottle, now full of saltwater, to bring me back up to dry land — waking me before I drowned.”

He went home to Tuskegee, where his 97-year-old grandmother gave him a pep talk and some no-nonsense advice: “Why don’t you get a good night’s sleep? God has your next move.”

Even for a reader who has never gone multiplatinum, embraced Nelson Mandela or performed in front of 2 billion people at the Olympics, these passages are, in many ways, relatable.

For Richie, that hiatus was a lifesaver.

“Every time you feel fear, step forward,” he said once again. “That’s what I keep in my mind now. Is today confusing? Yeah. Tomorrow may not be. Why? Because I faced today.”

Comments