Two exhibitions celebrate Chicago’s Latino communities

- The San Juan Daily Star

- Oct 22, 2025

- 5 min read

By TANYA MOHN

A sturdy kettle to make coffee for early-rising railway workers. A colorful cart of a paletero (ice cream vendor). A century-old lithograph of the patron saint of the Mexican people. These and other everyday objects and treasures will be on display in Chicago as two museums celebrate the city’s Latino communities.

“Aquí en Chicago” (“Here in Chicago”), a bilingual show that opens Oct. 25 and runs for more than a year — through Nov. 8, 2026 — at the Chicago History Museum, will explore the cultural heritage and traditions of Latino people. The idea developed after area high school students on a social studies field trip protested the lack of representation of local Hispanic history.

“We say that we are about sharing Chicago stories,” Elena Gonzales, the museum’s curator of civic engagement and social justice, said in a telephone interview, “but how can we do that if we’re leaving out a third of the city?”

“Rieles y Raíces: Traqueros in Chicago and the Midwest” (“Tracks and Roots: Railway Workers”), also bilingual and running from Nov. 21 to March 29 at the National Museum of Mexican Art, will highlight the history of regional Mexican and Mexican American railway workers.

“The exhibition is going to be about the lives of the people who built, worked to maintain and lived along the train tracks,” Cesáreo Moreno, the museum’s chief curator and visual arts director, said in a phone interview, “and how these people and families were able to create community and keep their culture alive.” (Admission to the museum is free.)

One neighborhood the railway workers helped form is Pilsen, where prominent murals reflect its largely Mexican heritage. The area is also home to both the National Museum of Mexican Art and the Instituto Justice and Leadership Academy, whose student protests in 2019 led to the Chicago History Museum’s “Aquí en Chicago” exhibition.

“There’s a long history that’s been overlooked,” said Lilia Fernández, professor of history at the University of Illinois Chicago and author of “Brown in the Windy City: Mexicans and Puerto Ricans in Postwar Chicago.” “Latinos have been a very important part of the U.S. workforce for decades. They have been in the Chicago area for well over a century. They came in significant numbers in the early 20th century, and in even greater numbers after World War II.”

The 4,000-square-foot “Aquí en Chicago” will examine the city’s immigrant lives with more than 700 artworks, photographs, clothing, personal items, protest posters and music. Items include quinceañera gowns for the traditional 15th-birthday coming-of-age celebrations for young women and a collection of 265 tiny terra cotta models of local landmarks, businesses and homes made in response “to feelings of historic erasure and being under threat of displacement,” Gonzales said.

The paletero’s cart that will be on display traveled some 100,000 miles over 35 years. “Anybody who’s been to Chicago knows that sound of the bells and the sight of the paletero or paletera, walking around the city, pushing the cart, selling frozen treats,” she said.

Interactive features will include a digital communities’ scrapbook that invites visitors to upload personal photos and a listening station where they can hear Latin American Indigenous languages spoken in the Chicago area.

Thematic sections will explore such issues as the challenges of housing inequality and how wars, work and sanctuary have been the main drivers in Latino immigration to Chicago.

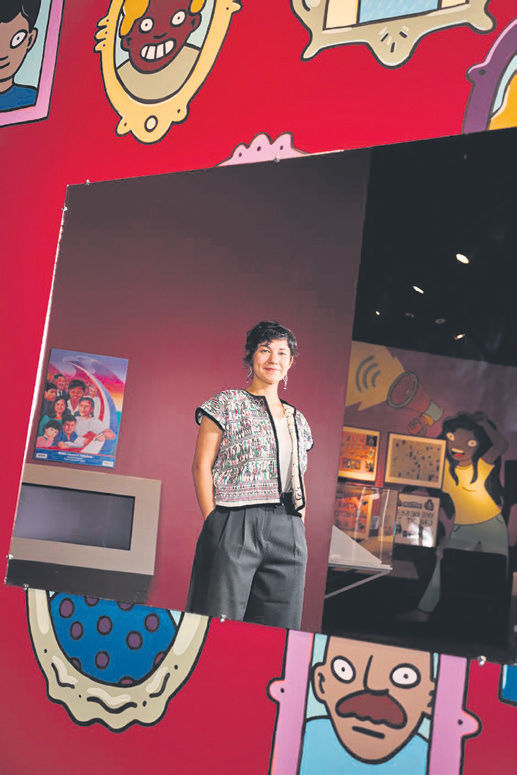

Cecilia Beaven, a visual artist from Mexico City who is based in Chicago and is the show’s co-designer, said the first goal was to establish the mood through color. “I started by creating a palette that is used throughout the exhibition,” she said, inspired by colors used all over Latin America for millennia. “They used colors coming from natural pigments, like seeds and flowers,” she said: blues from the añil flower, purples from the mollusk and reds from the cochineal insect.

Beaven painted a series of character-based murals. One is a reflection on identity and what it means to be from Latin America; another is on resistance and public protests. “It’s about having a voice and advocating for ourselves as Latin Americans,” she said.

About a third of the material on display will be on loan from the local community, and some items are accompanied by oral histories.

Antonio Alcala, marketing manager for Alcala’s Western Wear, a family business started in 1972 by his grandfather, donated the company’s first pair of custom cowboy boots, a shirt and a family member’s silver belt buckle. Originally from Durango, Mexico, his grandfather worked in the fields and in odd factory jobs and sold items from the trunk of his car: anything that it took to provide for his 11 children, Alcala said, “that was better than what he had back home.”

His grandfather eventually became a tailor and bought a store that sold Mexican-inspired and Western clothing. The items given to the museum, he said, symbolize his family’s legacy and commitment to hard work, as well as the determination and resilience of immigrants.

“My grandfather and parents always said, ‘You can’t take anything with you, but you can leave behind how people see and remember you,’” Alcala said.

More accounts of immigrant life emerge at the National Museum of Mexican Art. After moving to Chicago for jobs, “many railroad workers stayed and became part of the American dream,” said Alejandro Benavides, who curated “Rieles y Raíces” with Ismael Cuevas. “They were able to maintain their culture, their language and their faith because they lived together, many in boxcars alongside the tracks.”

Benavides and Cuevas developed an interest in the topic independently. Benavides lived near a former boxcar camp in Aurora, Illinois, and wrote “Olivia,” a fictional account of a young Mexican American girl who lived there. Cuevas began researching rail history at Amtrak, where he worked recently.

Photographs, paintings, linoleum cuts, works on paper, documents, census records and maps of railroad routes and migration patterns are among the items that will be on display, many obtained through a community collection process.

“How do we take that and shape it into a story?” Benavides said. “We want to make it family-friendly and visibly engaging.” Models of a train yard and boxcars are ways to do that, he added.

Informing the research for the exhibits were archival documents and accounts in books including “Mexican Labor in the United States” by Paul S. Taylor, Cuevas said. The author, he added, “literally was out in Chicago in the late 1920s interviewing people off the street.”

Other highlights include a black-and-white photo featuring a young woman playing music in front of a boxcar and the mandolin she used. “That instrument was used to tell stories and to carry on the culture, the songs that working-class people sang at a celebration or after a hard day of work,” Moreno explained.

Cuevas said, “We’re trying to find music of the era so that the visitor can listen to how it would have sounded 100 years ago.”

Another photo depicts a small chapel built inside a boxcar. In the background is an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, protector of the Mexican people. The original lithograph will be on display.

Comments