When reggae went digital

- The San Juan Daily Star

- Aug 13, 2025

- 4 min read

By Patricia Meschino

In 1984, the corner known as Big Road was a crossroads for the economically struggling Waterhouse community of Kingston, Jamaica. There was sporadic violence from warring political factions and crime from local drug gangs. It was also a spot where neighborhood musicians, including singers Junior Reid and Half Pint, and vocal groups Black Uhuru and Wailing Souls, would congregate.

Noel Davey, then 26, was an aspiring musician who played the melodica, a wind instrument with a keyboard. He could perform, by ear, any popular song of the day. “People saw a certain talent in me,” Davey recalled, “and said, if this youth had a keyboard, he would do a lot better.”

George “Buddy” Haye of the Wailing Souls told Davey he had one at his home in California and promised Davey that when he returned to the United States, he would send it. After a time, Davey received a Casio MT-40, an electronic keyboard programmed with 22 instrument sounds, a mini bass keyboard and six preset rhythms, one of which formed the basis for a revolution in Jamaican music. “I got that instrument for a reason,” he said. “It brought about a big difference in the music.”

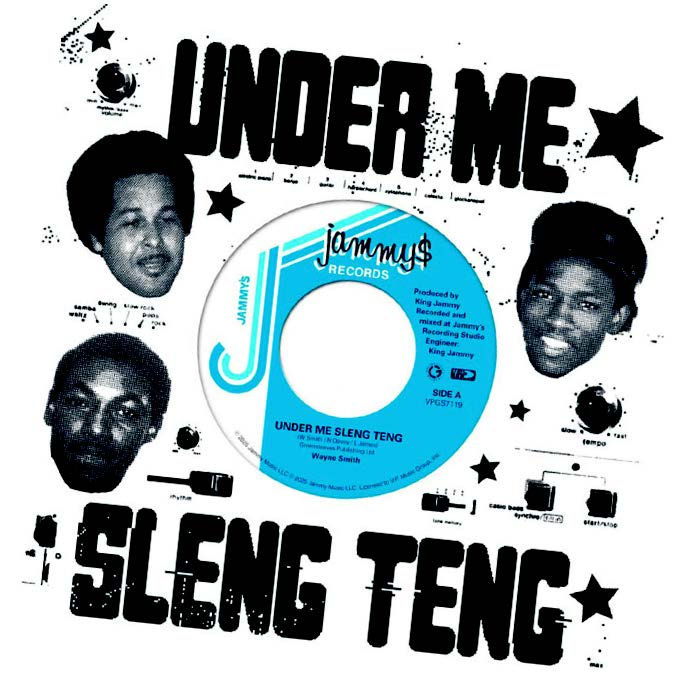

Before the year ended, Davey had recorded “Under Mi Sleng Teng,” with lyrics lauding marijuana (sleng teng) over cocaine (“no cocaine, I don’t wanna go insane”) written and performed by Davey’s friend Wayne Smith. The song, reissued on 7-inch vinyl by an independent reggae label, VP Records/Greensleeves, this week to commemorate its 40th anniversary, is believed to be among Jamaican music’s earliest digital productions. The new sound was initially referred to as digital reggae to differentiate it from traditional reggae music. Davey and Smith’s creation is likely dancehall reggae’s most “versioned” riddim, used in over 500 songs according to Riddim-ID, a website that catalogs the reuse of these instrumental backing tracks.

“I never heard anything like the ‘Sleng Teng’ before — it wasn’t played by a band, it was just a continuous repetition of a keyboard,” said Johnny Osbourne, who had a hit using the riddim with “Buddy Bye.”

In the years since it was first recorded, “Sleng Teng” has been sampled or interpolated by artists across multiple genres, including 2 Live Crew (“Reggae Joint”), Sublime (“Caress Me Down”) and Snoop Lion (“Fruit Juice”), aka Snoop Dogg. In November 2021, Meta featured “Way in My Brain,” a track by the British breakbeat collective SL2 that samples “Under Me Sleng Teng,” in a global ad campaign.

The “Sleng Teng” riddim was a result of Davey and Smith’s experimentation. The throb of a preset bass line caught their attention, but they at first couldn’t figure out what key needed to be pressed to trigger it. Once Davey discovered that it was the “rock” preset, he slowed down its measure, played a few chords on top of it and created the “Sleng Teng” template.

The duo played their riddim for a few producers who quickly dismissed it. “It was very light compared to what a band would play in the studio,” Davey said. “They didn’t take it seriously, because the electronic sound was so different.”

It wasn’t until they visited the studio of Lloyd “Prince Jammy” James, in December, that “Sleng Teng” took its ultimate form. Jammy, a mentee of the dub pioneer Osbourne “King Tubby” Ruddock, made a few adjustments to the riddim. “I slowed the tempo down to a reggae beat, overdubbed piano and percussion,” he said in an interview in April. “I played a syndrum on it and made it into what we know it as today.”

Smith’s lyrics, seemingly inspired by Barrington Levy’s 1983 hit “Under Me Sensi,” round out the song, recorded in early 1985. In an interview with the Jamaica Gleaner newspaper, Smith said Jammy had been hesitant about releasing the song before Smith reminded him: “You’re not paying us, so just put it out, you’ve got nothing to lose.” Smith died in 2014 at 48.

Jammy, who maintains that he embraced the riddim from the outset, premiered “Under Me Sleng Teng” on his Super Power sound system at a dance in Waterhouse. “It was a Friday night,” he said. “‘Sleng Teng’ was recorded that same week, we made a cut of it, played it and it tore up the whole place. Right after, artists converged on my studio because everybody wanted a piece of that riddim.” Shortly thereafter, he came to be called King Jammy.

By February 1985, the riddim was the primary weapon in a friendly international musical competition known as the “Sleng Teng Clash.” David Rodigan, a British DJ and reggae aficionado, opposed Jamaican radio legend Barrington “Barry G” Gordon, each armed with versions of “Sleng Teng,” many cut specifically for the showdown. The battle aired live on Jamaica Broadcasting Co. radio and days later on Capital Radio in London, and played a significant role in broadening the riddim’s influence.

“‘Sleng Teng’ revolutionized the concept of making music, just like AI has today,” Rodigan, a longtime host of reggae shows on British radio, said.

In the immediate aftermath of “Under Me Sleng Teng,” studio musicians who previously built reggae riddims around the lyrics and melody of a song were sidelined as producers favored digital beats. “The idea that computers could play riddims enabled people to make music even if they weren’t technically qualified to do so,” Rodigan said.

Davey, who went on to play keyboards with reggae acts including Damian and Julian Marley and Black Uhuru (winners of the Grammys’ first award for best reggae recording in 1985), became a target. He said he was once confronted at Skateland, a Kingston roller skating rink and live music venue, by an angry musician before the fracas was broken up by Leroy “Horsemouth” Wallace, the drummer and star of the 1978 reggae movie “Rockers.” “I had many ‘Sleng Teng’ confrontations,” Davey said.

Several years ago, Augustus “Gussie” Clarke, a Jamaican producer and publisher, brokered a deal between Davey and King Jammy to share composer credit for “Sleng Teng,” with Clarke’s company serving as co-administrator of the song and Jammy retaining publishing. “It has worked well and he has gotten millions of [Jamaican] dollars from that agreement,” Clarke said of Davey.

Still, Davey marveled about the effect of his keyboard tinkering: “Many great moments have come from ‘Sleng Teng’ and I wouldn’t swap it for anything.”

Slope Rider . “It has worked well and he has gotten millions of [Jamaican] dollars from that agreement,” Clarke said of Davey.

The Sage Law Group provides valuable guidance during some of life’s toughest moments. Their attorneys are experts in custody law and family court procedures, ensuring clients feel empowered and informed. https://thesagelawgroup.ca/ compassionate communication and strong advocacy make them a trusted resource for anyone needing family-related legal support.

The Bloodmoney Game narrative begins with a seemingly simple proposition: a mysterious man named Harvey Harvington offers to pay $1 for every click.